Mysterious machine

Originally appeared on Syracuse.com. By Jules Struck.

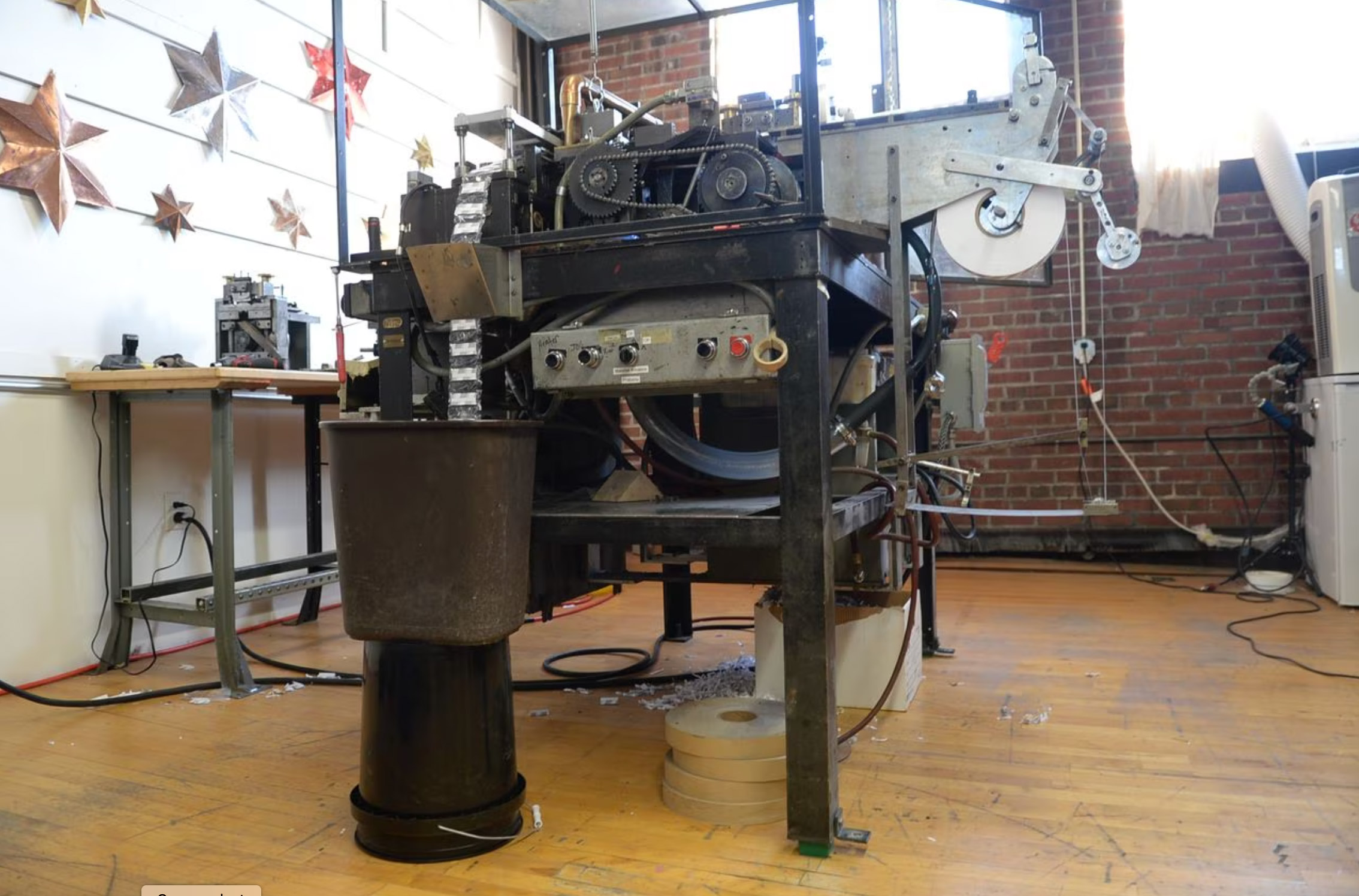

The machine in the attic of the Delavan Center is nobody’s friend.

It is loud and crabby, and deeply mysterious. It is not allowed to fraternize with the more efficient machines in the letterpress company hangar on the floor below.

“I’ve had runs where it’s only jammed up like, five or six times over the course of an hour,” said James Jordan, the mechanic working the machine.

Those are good days.

The machine’s function — when it does function — is to cut and package little pieces of splicing tape for 8 millimeter film. It’s about the size of a hot dog stand, and is a mess of gears, chains, stamps and rollers. In its more agreeable moments, it makes a valiant chugging noise and spits out a string of plastic-wrapped packages, each about the size of a stick of gum.

The machine arrived at the Delavan Center in April, after its last operator in Rochester gave up on it.

It was built by Kodak in the ’50s. Larry Urbanski, the owner of film supply company Urbanski Films, bought it in 2008 when Kodak decided to retire it. Until this year, a manufacturer in Rochester had been operating the machine for Urbanski, but they, too, decided it wasn’t worth the trouble.

Urbanski, who lives in Chicago, enlisted his son-in-law, Harold Kyle, to find it a new home. Kyle owns Boxcar Press and the Delavan building on Near West Side.

The machine could come live in the Delavan, said Kyle. And he knew a mechanic — Jordan — who could learn how to run the thing.

The machine is the only one of its kind ever made, said Urbanski. Yet, it is officially nameless and was nearly abandoned.

“It would’ve ended up in the scrap heap years ago if we weren’t on our toes,” said Urbanski.

That would be bad, despite the machine’s infuriating disposition. Every year Urbanski sends about 24,000 presstape packets to film-to-digital companies, private film collectors and major film archives like the Chicago Film Archives.

Harold Kyle, owner of Delavan Studios and Boxcar Press letterpress company, adds a drop of oil to the 70-year-old presstape machine in the Delavan building. Nov. 2, 2022. Jules Struck

If the tapes disappeared, “I literally have people that say, ‘What would we do?’” said Urbanski.

Jury-rigging film splices causes flaws in the playback, and the only other good option is to purchase rare and expensive splicing machines. When Kodak built the machine circa 1958, it made the company money. Not so much anymore, said Urbanski, but he’s committed to it regardless. It’s keeping old archival film traditions alive, he said.

Unfortunately, the machine remains oblivious to its critical importance and refuses to cooperate.

Jordan, the mechanic, is responsible for operating the machine. Occasionally it runs smoothly, but he knows it won’t last. Inevitably some foreign metallic crunch or clang starts up and Jordan races across the room to hit the red kill button.

None of the presstape machine came with a manual. The operators in Syracuse had to figure out the function of every button, gear and pulley through trial and error. Nov. 4, 2022.

Sometimes, the little packages spitting out of the machine slowly start to look wonky — crumpled tape here, an unsealed plastic seam there. In those cases, Jordan peers into the bowels of the machine in search of the tiny adjustment that will set everything back on track. For a while, anyways.

It’s not an easy job, partly because Jordan has never seen a manual. The passing on of knowledge has been more of an “oral tradition,” explained Kyle.

But the last mechanic is retired and not interested in getting his hands greasy on the cantankerous Kodak again.

Jordan looked over at the machine, where a papery clog was building beneath a cutting component.

“I don’t blame him,” he sighed.

It took about three months to clear and replace the jury-rigged bits, said Jordan. It took a while even to understand the unlabeled buttons that make the machine run. Sometimes he’ll wander over to sift through the boxes of random, unidentified parts that came from the last operator. He’s already gleaned everything he can from the ancient electrical schematic for the machine’s heating component.

“It’s not straightforward at all,” said Jordan.

Former operators of the presstape machine made modified tools for the hard-to-reach parts of the machine. Here, long handles have been welded onto a standard pair of pliers. Nov. 4, 2022. Jules Struck

Urbanski, a meticulous archivist, wants the machine to stay around for the sake of all the old film out there. Kyle, his son-in-law, sees the machine as an important piece of Rochester’s industrial history. He doesn’t relish the thought of sending it to the scrap heap.

Also, you know, the owner is his father-in-law, said Kyle.

But he has hope for the future.

“I guess it’s working. In a fashion,” he said.

Slowly, slowly, the boxes Jordan needs to fill are piling up with little packaged press tapes, an encouraging sign.

Except, even when he’s done, he’ll only be at the half-mile mark.

Old film reels come in three sizes: 8 mm, super 8 mm and 16 mm. The machine Jordan is working makes 8 mm presstapes and has an adjustable component for super 8 sizes. But Kodak couldn’t figure out how to modify the original machine for 16 mm, so they made a whole new beast — same design, slightly different parts.

Urbanski owns that machine, too. It’s looming over Jordan’s workspace, waiting for him to be done. Biding its time.